Battle for Hill 70

In April, 1917 the Canadian Corp, operating as a unit for the first time, had successfully captured Vimy Ridge from the Germans. This was the first major victory for the Allies at that point in the war and resulted in not only the acquisition of more ground than any prior Allied offensive along the Western Front, but of arms and prisoners of war as well (Nicholson 266).

As a result of the attack at Vimy, Lieut.-General Sir Julian H. G. Byng, future Governor General of Canada and commander of the Canadian troops, was ordered to take command of the British 3rd Army (Nicholson 283). His replacement for the Canadian Corps was Sir Arthur Currie, (283) newly promoted to Lieut.-General and knighted by King George V. For the first time in history, a Canadian was in command of all Canadian troops.

Before the war, Currie was a real-estate promoter in Victoria, BC, and shortly after he was promoted it was brought to light that he had used government funds to pay off some business debts. To avoid further scandal, Currie quickly borrowed some money and replaced the missing funds[1]. Currie’s promotion also caused some strife for the Canadian authorities due to the fact that the promotion had been made by Field-Marshall Sir Douglas Haig, who did not have the authority to promote inside the CEF. The promotion was later approved anyway (284). Currie was officially promoted on the 9 June 1917, and was thus in command of the Canadian Corps (Nicholson 284).

Currie was a superb tactician, and widely thought to be one of the best military minds of all time. He was incredibly sensitive about the use of troops, and his actions as commander have been attributed to saving thousands of lives. However, he was also incredibly insensitive and awkward in his dealings with the men under his command and was subsequently disliked by the troops.

On July 7th, 1917 Currie was ordered to take the town of Lens in northern France (284). The town was of strategic importance, with the Germans needing it for its rail access, while the British wanted it for its coal, which they needed to support war manufacturing. Additionally, the British wanted to use the attack as a feint, committing German troops to Lens while the British and French attacked in the Somme area.

Currie was not confident about the decision for a frontal attack on Lens. He felt that the troops could take the town, but would then find itself under attack from the high ground that surrounded the town and believed that the losses would be unacceptably high. Currie instead proposed to take Hill 70, the high ground to the north of Lens (285). He knew that it would not be an easy objective to take, and that causalities would be high, but they would be considerably less than if they left the hill in the hands of the Germans. Currie argued that the Germans would attempt to retake the hill and the Canadians would have the advantage of high ground and would be able to inflict significant losses on the Germans. The British Army structure did not appreciate Generals changing orders instead of following them, and the issue was raised to Field Marshall Sir Douglas Haig, commander of the British forces. Haig approved Currie’s plan of attack on Hill 70, but predicted that it would fail.

Hill 70 was a perfect defensive position. It was a maze of deep trenches and dugouts and included deep mines that had been dug in peacetime and could protect the defenders. Coiled barbed wire, up to 5 feet in height was in front of the trenches would make a frontal attack difficult. Machine guns were deeply entrenched in the slopes, inside of pill-boxes reinforced by concrete[2]. Additionally, in July 1917 the Germans had introduced flame-throwers and mustard gas, which blistered any portion of exposed skin it made contact with. Overall, Hill 70 wasn’t an enviable target to be given.

Preparations for the attack were extensive. Due to bad weather that postponed the attack until mid-August, the Canadians kept themselves busy (286). As they had done at Vimy, an area behind the lines was laid out to represent Hill 70, and units practiced the attack until every section knew exactly what they had to do (287). Additionally, the hill and the surrounding area was subjected to ongoing bombardment, raids and gas attacks (286). The gas, being heavier than air, would have sunk to the lowest areas of the trenches and caverns, making it very uncomfortable for the German defenders[3].

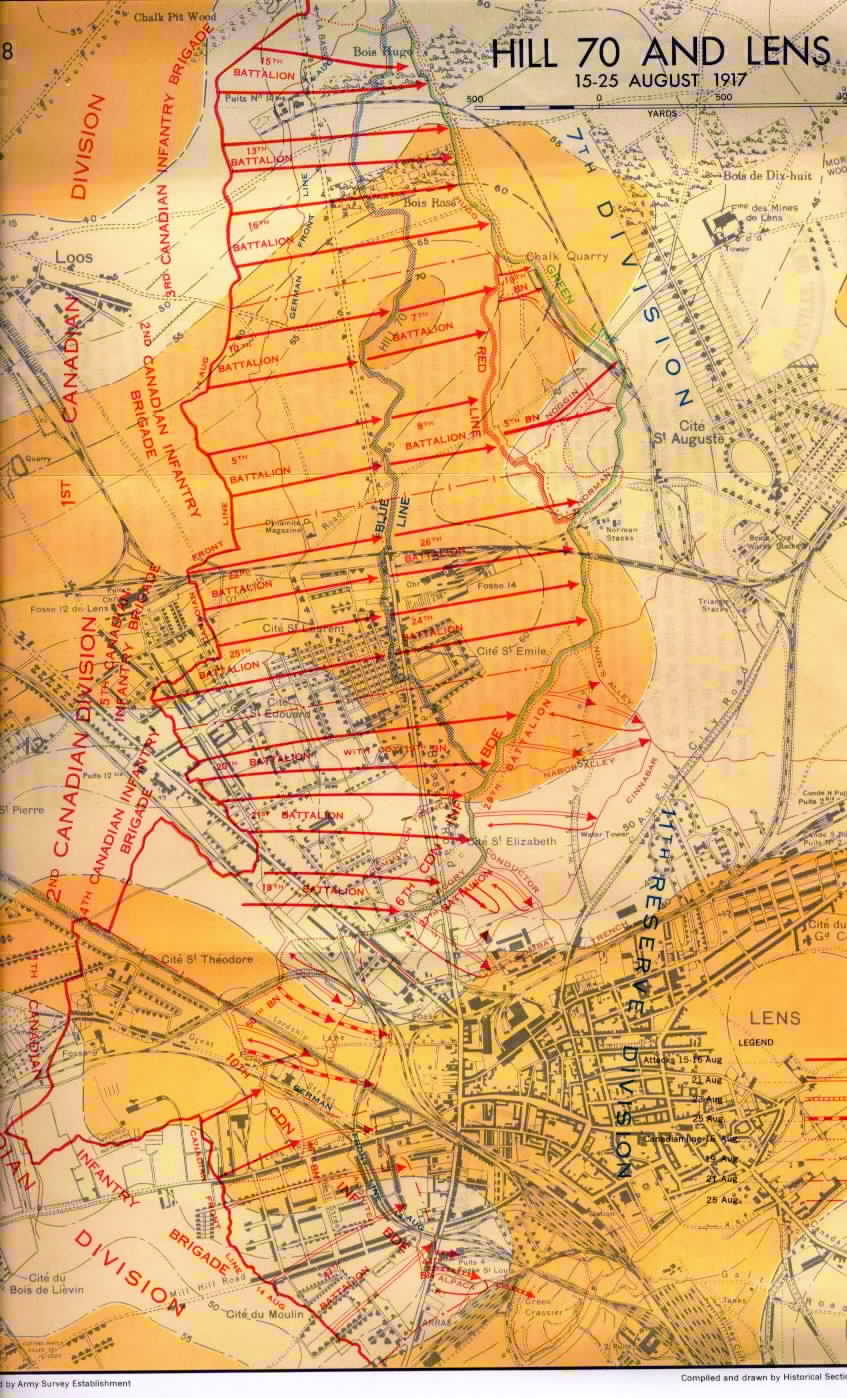

On the evening of 14 August the attack commenced with the bombardment of the hill by the Canadian artillery, damaging the trenches and blowing holes in the defensive wire. At 4:25 AM, dawn of August 15, the Canadians went over the top, with the 1st Division on the left, the 2nd Division in the center and the 4th Division, in a largely diversionary attack (289), on the right. The 3rd Division was kept back in reserve. The ten battalions of men advanced up the hill, the 7th and 10th battalions being assigned the high points on the hill, closely following a rolling barrage by the artillery. They took the first objectives in twenty minutes[5]. The Canadians introduced a new tactic to demoralize the Germans. Drums of burning oil were dropped into the deep trenches, spreading flame and smoke over the hill (287). Another feature of the attack on Hill 70 was the close co-operation between the Air Force and the Artillery. Low flying aircraft spotted pockets of resistance and radioed the co-ordinates back to the artillery who responded with prompt shelling.

By 9:00 am, the Germans had begun to counter-attack, but were consistently fought off by the Canadian troops on the hill and the artillery in support (290). The Canadian artillery crews suffered heavily. The Germans recognized that without them the attack would fail, and started a barrage of high explosive and Mustard Gas shells. The day was hot. Being forced, because of the gas, to work fully clothed and with gas masks, several men died from heat prostration[6]. Wearing a gas mask rendered the men half blind, but removing them caused a horrible death as the Mustard Gas seared their lungs. Many men had to remove their masks, whether to accurately aim the guns or to extricate themselves from holes or wire on the hill slopes, and suffered from facial and internal blistering as a result.

The Germans were determined to retake the hill. The Canadians were subjected to intense artillery shelling, suffered from lack of rations and water, and, when ammunition ran low, resorted to attacking with bayonets[7]. On August 21st, the 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles took over the front lines. They described the situation: “At this time the Hill presented every aspect of a fierce and sanguinary battle; most of the German trenches had been crumpled in by our shell fire, while everywhere one went were dead Huns and, in some cases, Canadians”[8].

In total, the Germans counterattacked 21 times, with the last taking place at dawn on August 18th. The Canadians successfully repulsed them all (290).

The attack on Hill 70 resulted in 1,505 Canadian men killed, 3,810 wounded by fire, 487 wounded by gas and 41 prisoners to the Germans (290, 292). The majority of the casualties were from the first day of the attack. In some cases companies reached, and held their objectives while sustaining over 70% casualties[10]. The Germans had committed 5 divisions in an attempt to hold Hill 70, but were badly battered by Currie’s troops (297), with approximately 20,000 casualties and 970 Germans taken prisoner.

Lens was not taken, however holding the high ground of Hill 70 seriously impacted the German position and gave Canadian troops a significant tactical advantage during the German offensive of 1918 (297).

The taking of Hill 70 cemented the reputation of the Canadian troops. Douglas Haig was wrong in his prediction, while Currie had proven himself a superior tactician through what he described as “altogether the hardest battle in which the Corps has participated,” and was praised by the G.H.Q. as “one of the finest performances of the war.” (292) The Canadian troops earned five Victoria Crosses during this four day period, including Private M.J. O’Rourke, who saved countless lives due to his enduring heroism (290).

Attack on Hill 70

Footnotes:

[1] Marching To Armageddon, Desmond Morton and J.L. Granatstein, page 161

[2] 31st Battalion CEF, H.C. Singer, page 234

[3] 31st Battalion CEF, H.C. Singer, page 238-239

[4] Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War, G.W.L. Nicholson

[5] Morton says 20 minutes, Singer reports 16 minutes.

[6] When your number’s up, Desmond Morton, page 134.

[7] Canada’s Black Watch, 1862-1962, Paul P. Hutchison Page 99

[8] The 2nd Canadian Mounted Rifles in France and Flanders 1914-1919, Lt.-Col. G Chalmers Johnston, D.S.O., M.C.(CEF Books reprint version 2003) Page 51.

[9] Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War, G.W.L. Nicholson

[10] Narrative of Battle for Hill 70, 10th Infantry Battalion CEF

Works Cited:

B: Nicholson, G.W.L. Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1919. Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1962.

N: G.W.L. Nicholson, Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War: Canadian Expeditionary Force 1914-1919 (Ottawa: Queen’s Printer, 1962),

SN: Nicholson, Official History of the Canadian Army in the First World War,